How far are you willing to travel for groceries? Now consider this: Let’s say you didn’t have access to reliable transportation and had to rely on public transportation. What if you had a family you were responsible for after coming home from your full-time job? These may not be questions you have ever needed to contemplate, but for many families living in Philadelphia’s food apartheid, choosing between feeding your family healthy food or feeding them at all is a daily battle. This reality leads many to eat overpriced junk food from corner stores and fast food places with limited selection just to get by.

As I touched on in my previous post, “Why Food Sovereignty Matters in Philadelphia,” food inequities are a concern in many areas of Philadelphia, but racial disparities in access to food are a nationwide issue. Despite areas suffering from equal levels of poverty, research shows that black areas have the fewest supermarkets while white regions have the most. To examine why this is the case, we must look through our country’s extensive history of excluding people of color and why the occurrence of food apartheid is no mistake.

White Flight and Redlining: A History of Exclusion

The post-World War II era saw a mass migration of white Americans from cities to the suburbs, a phenomenon known as white flight. In search of exclusivity and a higher social status, many whites moved after desegregation because of their uncomfortability with interacting with African Americans. This white flight set the stage for decades of divestment of black and brown communities.

On a national level, government institutions were fighting to deepen the racial divide by instating policies that justified discrimination. African Americans pursuing buying houses in the suburbs were turned away due to the Federal Housing Administration’s claim that the property values of the homes they were insuring would be at risk. Even in predominantly black areas, redlining made homeownership out of reach for many people by refusing to insure mortgages in or near black areas. Consequently, African Americans and other people of color were left out of the new suburban communities and access to wealth, leaving supermarket developers searching for a new consumer market.

The Ideal Consumer

As suburbanization continued through the latter half of the 20th century, supermarket chains followed their predominantly white customer base, leaving urban centers behind. In the 1980s, a wave of mergers and consolidations within the grocery industry further reduced the number of stores in cities. With fewer, larger corporations controlling the market, grocery chains closed urban locations in favor of opening expansive, car-dependent stores in suburban areas. You could argue that the supermarket chain’s relocation decision was purely financial, but after hearing Michael Nutter’s story, you may change your mind.

Former mayor of Philadelphia, Nutter, fought tirelessly to bring a grocery store to a predominantly black area of Philadelphia. Despite advocating to virtually every major grocery retailer in the country, it took nearly eight years for a retailer to open in the region. According to him, their unwillingness to accept his offer was borne out of the ideology that black and brown communities don’t spend money. This racist, stereotypical mindset is extremely dangerous and deeply affects communities that are deemed unworthy by supermarket developers.

How Food Apartheids Affect Communities

Lack of access to national and regional supermarkets means communities miss out on a variety of nutritious food at fair prices. Eating a wide range of fruits and vegetables is the key to a healthy life, so, as a result, these communities tend to have higher rates of type 2 diabetes and hypertension. Furthermore, most supermarkets are full-service with pharmacies and minute clinics attached to them, so people can easily access resources to maintain their health. Therefore, the scarcity of supermarkets perpetuates a cycle of health issues through lack of nutrition while also making it more difficult for people to get professional help for their ailments.

Looking Forward

The irony of living in food apartheid is that it is entirely preventable and should never have occurred. We can’t change the past, but with your help, we can ensure that future generations can access nutritious food, no matter where they live.

If you believe you live in a food apartheid in Philadelphia, use this interactive map to check your neighborhood food landscape using this interactive map. Next, Look into affordable delivery services. I recommend Dinnerly, which offers affordable meal kits for any dietary restrictions.

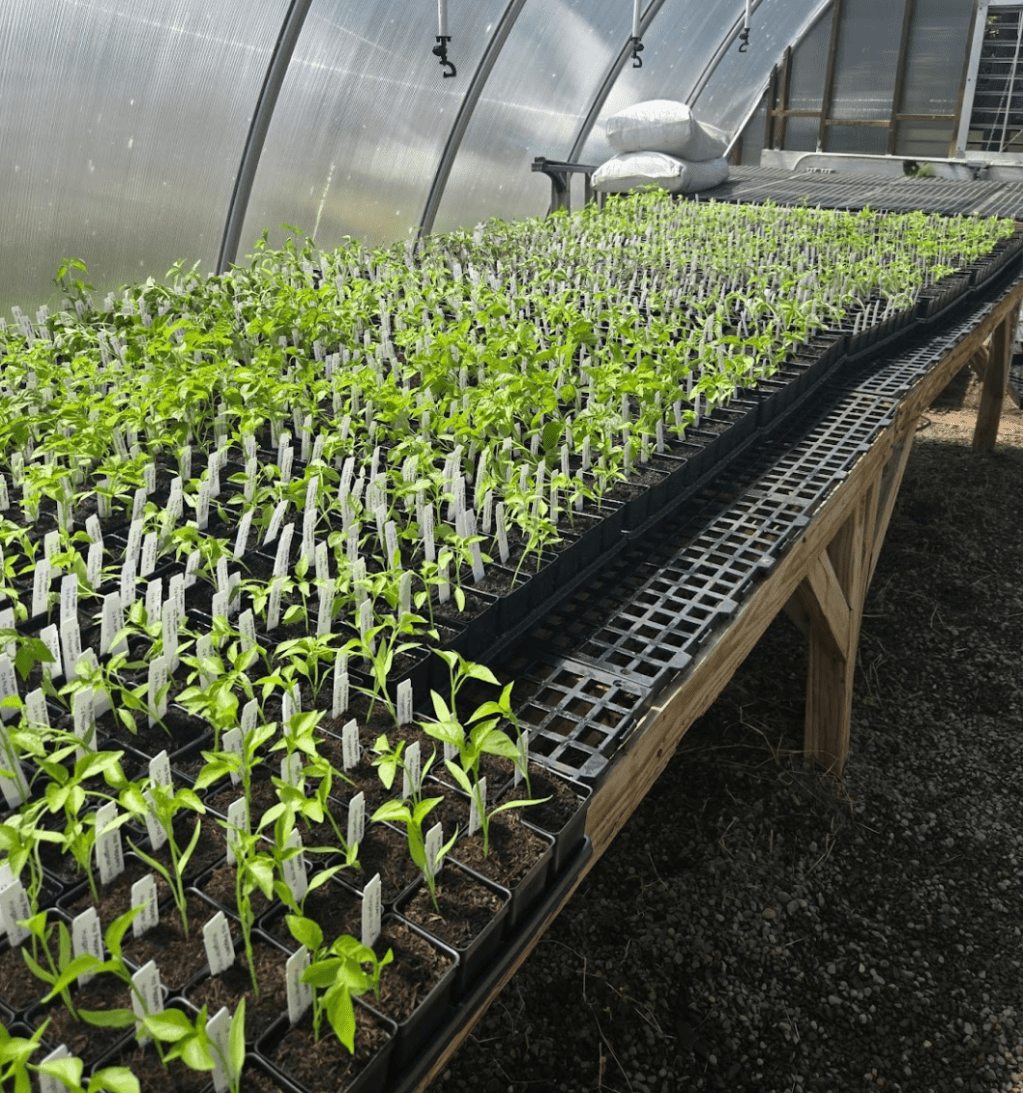

Support food initiatives in your area by buying local and volunteering your time. A great place to start is looking into community gardens. From working in the garden or offering your knowledge to teaching courses, Sanctuary Farm in North Philadelphia is always open to a helping hand!

If you have an idea for a healthy food business in your neighborhood, contact the Department of Commerce for support and advice. You can reach a Business Services Manager at 215-683-2100 or Business@Phila.gov.

Lastly, subscribe to my blog to receive more tips on how you can help fix the food inequity crisis in Philadelphia.

Leave a comment