Before getting into the nitty-gritty, we must have a baseline understanding of food sovereignty. I see no better source than Master Gardener Andromeda Jackson. As a Master Gardener, Jackson has completed numerous hours of research and study on food sovereignty and now hosts events where they educate the public on the topic. Therefore, they are the perfect starting point for my research.

Simply put, food sovereignty is the fundamental right of all people to have healthy, accessible, and culturally appropriate food. However, Jackson emphasized that the concept extends beyond empowering local food producers to produce and distribute nutritious food. Citizens should have the tools to create and distribute locally-grown food to their communities and reclaim control over their food systems.

After getting a baseline understanding from Jackson, it was time to research the state of Philadelphia’s food landscape. Why food sovereignty is a worthy cause in Philadelphia is a complex topic, requiring us to examine the city’s unique neighborhood disparities, economic landscape, and health outcomes. If food sovereignty wasn’t on your radar before, I guarantee that after reading my findings, you’ll be ready to join the cause.

The Divide: High-produce vs. Low-produce supply

Philadelphia’s food environment is skewed toward unhealthy options. Low-produce supply stores—those that stock mainly processed, high-calorie, and low-nutrient foods—vastly outnumber stores offering fresh produce. This imbalance affects everyone but disproportionately impacts lower-income neighborhoods, where more than 80% of food retailers primarily stock unhealthy options. Only 1 in 9 stores in the average neighborhood offer significant amounts of fresh produce.

The result? 63% of Philadelphians live in areas oversaturated with unhealthy food options, where more than 20 low-produce supply stores are within walking distance. These areas, often labeled as “food deserts,” would be more accurately described as zones of food apartheid, which means that these disparities are not natural, but are the result of social and structural policies that have historically excluded marginalized communities from accessing healthy food.

Power, Land, and Health Disparities

Central to food sovereignty is power. Land, historically, has been a symbol of wealth, power, and stability. Controlling land and food production gives communities greater political and economic power. However, black and brown communities in Philadelphia never had the opportunity to gain land ownership and have, therefore, been unable to grow and distribute fresh food in their own backyards. This food sovereignty gap directly contributes to community health detriment. Diabetes, heart disease, and other conditions related to poor diet and limited access to healthy food remain troublingly high in Philadelphia.

The CDC reported diabetes has grown by more than 50 percent in the last five years. Hospitalizations for diabetes are 75 percent higher in Philadelphia than in the rest of Pennsylvania. Furthermore, two-thirds of adults and 41 percent youth in the city are overweight or obese.

These figures highlight food inequity as a source that leads to the development of chronic health conditions that disproportionately affect communities of color.

Rising Grocery Costs

Meanwhile, the financial burden of buying healthy food further exacerbates the problem. With inflation driving up grocery prices, fresh produce is becoming even more inaccessible. In just one recent month, egg prices exploded by 8.2%, which is the highest increase in two decades. Beef, coffee, and non-alcoholic beverages have all seen significant price jumps, leading to the largest monthly grocery price increase since early 2023.

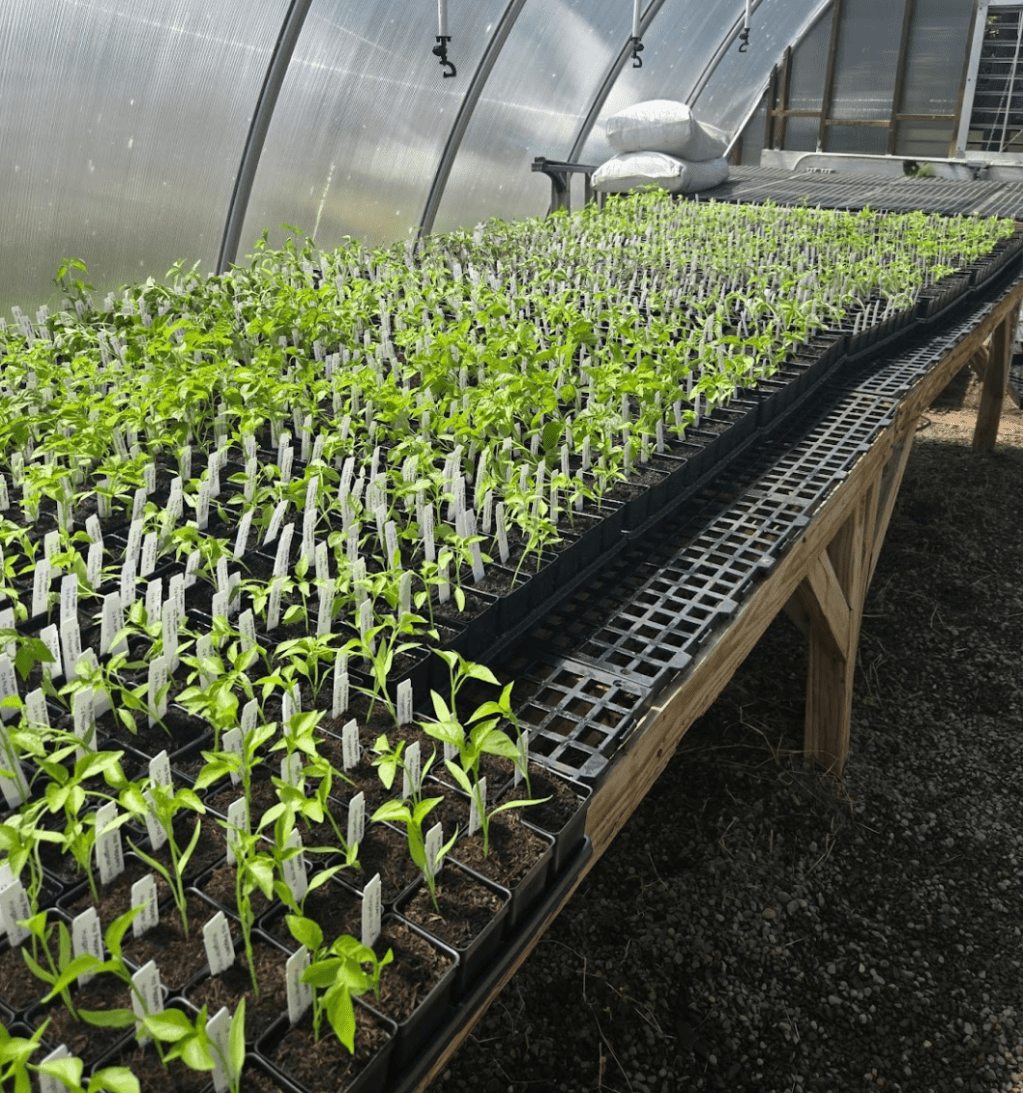

To put it into perspective, purchasing one pound of organic tomatoes from Whole Foods costs $3.99, while a packet of heirloom tomato seeds costs $4.99 and can yield 10 to 15 pounds per plant. This highlights the potential of urban farming and community gardens as sustainable solutions to food insecurity.

Conclusion

Philadelphia doesn’t have a food shortage—it has a food access problem. By promoting food sovereignty, you are distributing power to every individual and community to get the tools, education, and resources it needs for nourishment. Beefing up the food supply is not only a matter of nourishment, it also means choice, well-being, and power in life. And now that we have a basis for food sovereignty, we can continue learning about ways we can improve Philadelphia’s food inequities.

Leave a comment